|

|

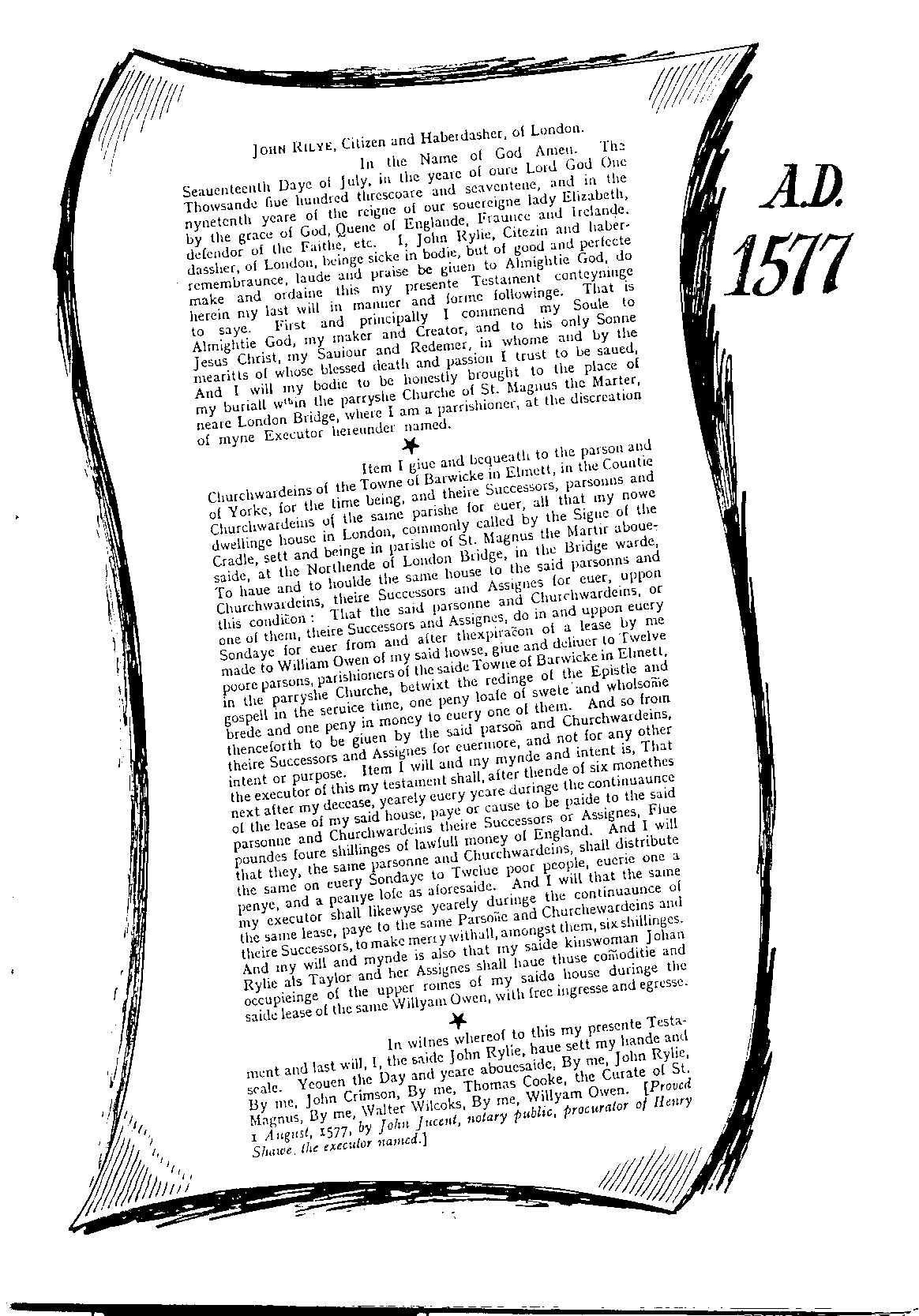

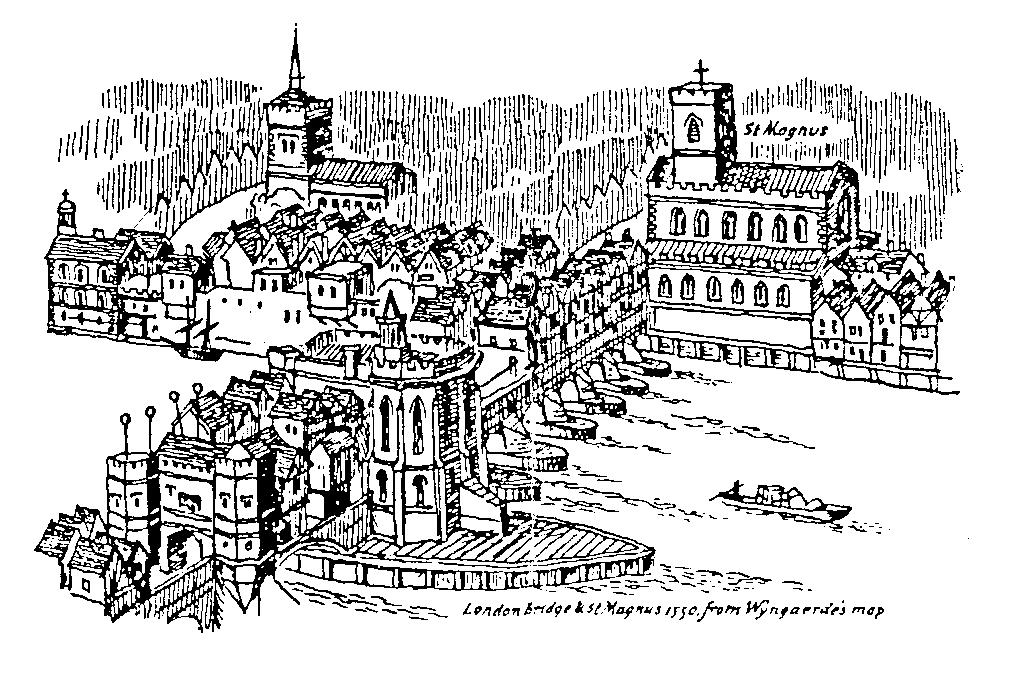

THE Church of St. Magnus the MartyrSituated in Lower Thames Street is the

Church of St. Magnus the Martyr where

John Rylie worshipped, and where he was

buried in accordance with his will.

Even in his day, it was old, the

first church to be built here was of

Saxon or Danish origin. This is the

Church of the Worshipful Company of

Fishmongers due to its proximity to

the river and Billingsgate, London's

landing port and market for fish since

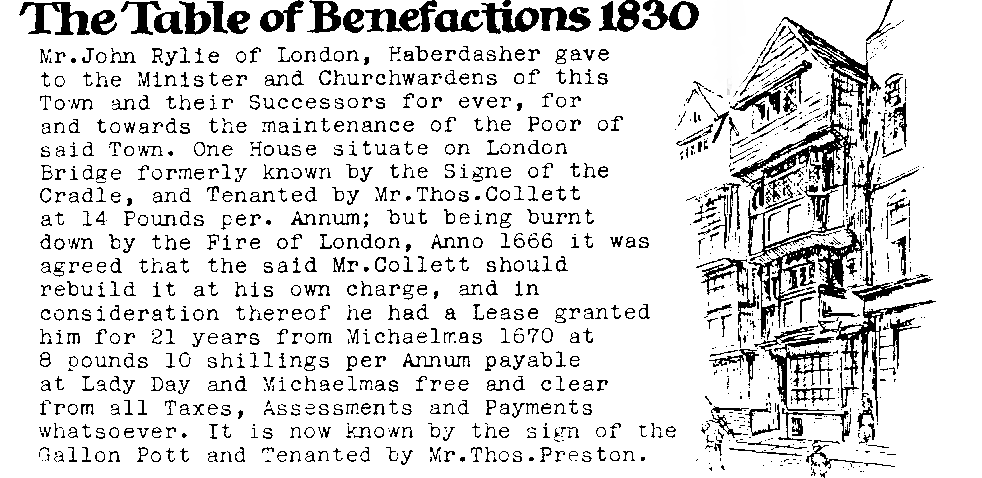

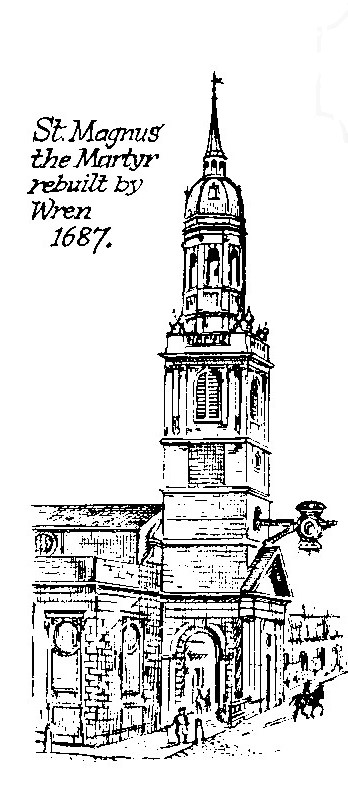

at least Saxon times. Over the years the Church became wealthy through many bequests, which included tenements on London Bridge. In 1234 it was enlarged, and in 1598, John Stow in his survey of London, described it as "a fair parish church in which have been buried many men of good worship whose monuments are for the mos t part effaced". Miles Coverdale who made an English translation of the Bible in 1532 was Rector for a short time, and is buried there. The church was repaired between 1623 and 1629 but consumed by the Great Fire of 1666. In fact being close to the source of the fire it was one of the first destroyed. It was then rebuilt by Wren in a very different style, this took place between 1671 and 1687 at a cost of £9,879. In 1886 the population of the parish was only 837. In the century that followed the numbers continued to decrease, until today the church mainly caters for city workers and visitors. It is beautifully maintained and well worth a visit. |