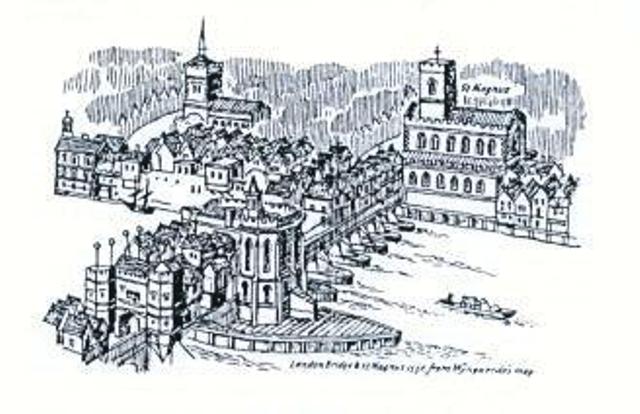

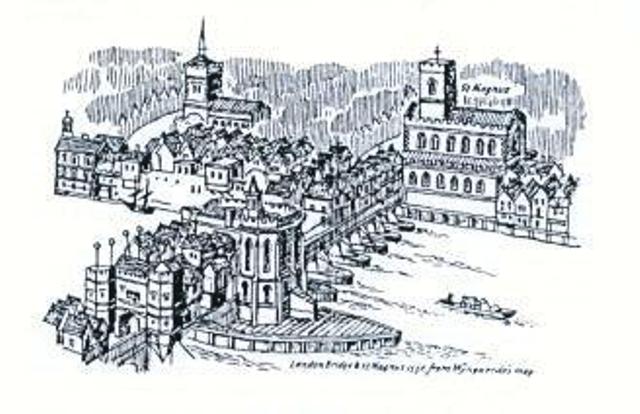

| "Mr. John Rylie of London, Haberdasher gave to the Minister and Churchwardens of this Town and their Successors for ever, for and towards the maintenance of the Poor of said Town. One House situate on London Bridge formerly known by the Signe of the Cradle,... " |

| " Mr Wray in behalf of the Parish of

Berwick (sic) in Elmet attended and the

Estimate of Mr Henry Adkins his Surveyor was

delivered in and read as follows Made a Survey in order to set a value of one Brick House of Forty pounds p(er) annum situate at the North end and on the West side of London Bridge and now in Possession of Mr George Thorp together with the Freehold and declared the same to be worth the Sum of Six hundred and thirty Eight pounds as witness my hand this 10th May 1762 Henry Adkins And Messrs. Dance and Taylor Surveyors to the Committee acquainted them that they had not been able to settle the affair with Mr Adkins and that they apprehended the House was not worth above half the Money Resolved that the matter be left to a Jury" |

| "The Rev. Mr. Wray received of the Churchwardens Five Pounds, five Shillings, which was agreed upon by the Parishioners for his trouble at London about the said messuage upon London Bridge." |

| 'to choose Trustees in Trust for a parcel of freehold ground called Mapplegate Flatt lying in Barwick aforesaid lately purchased of William Eamonson Gentleman of Lazincroft in the said parish for the sum of three hundred pounds being the money rising from the sale of a house on London Bridge belonging the poor of Barwick in Elmet'. |