The History of Barnbow

Part 1. THE GRENEFELD YEARS

from The Barwicker No. 57

Mar. 2000

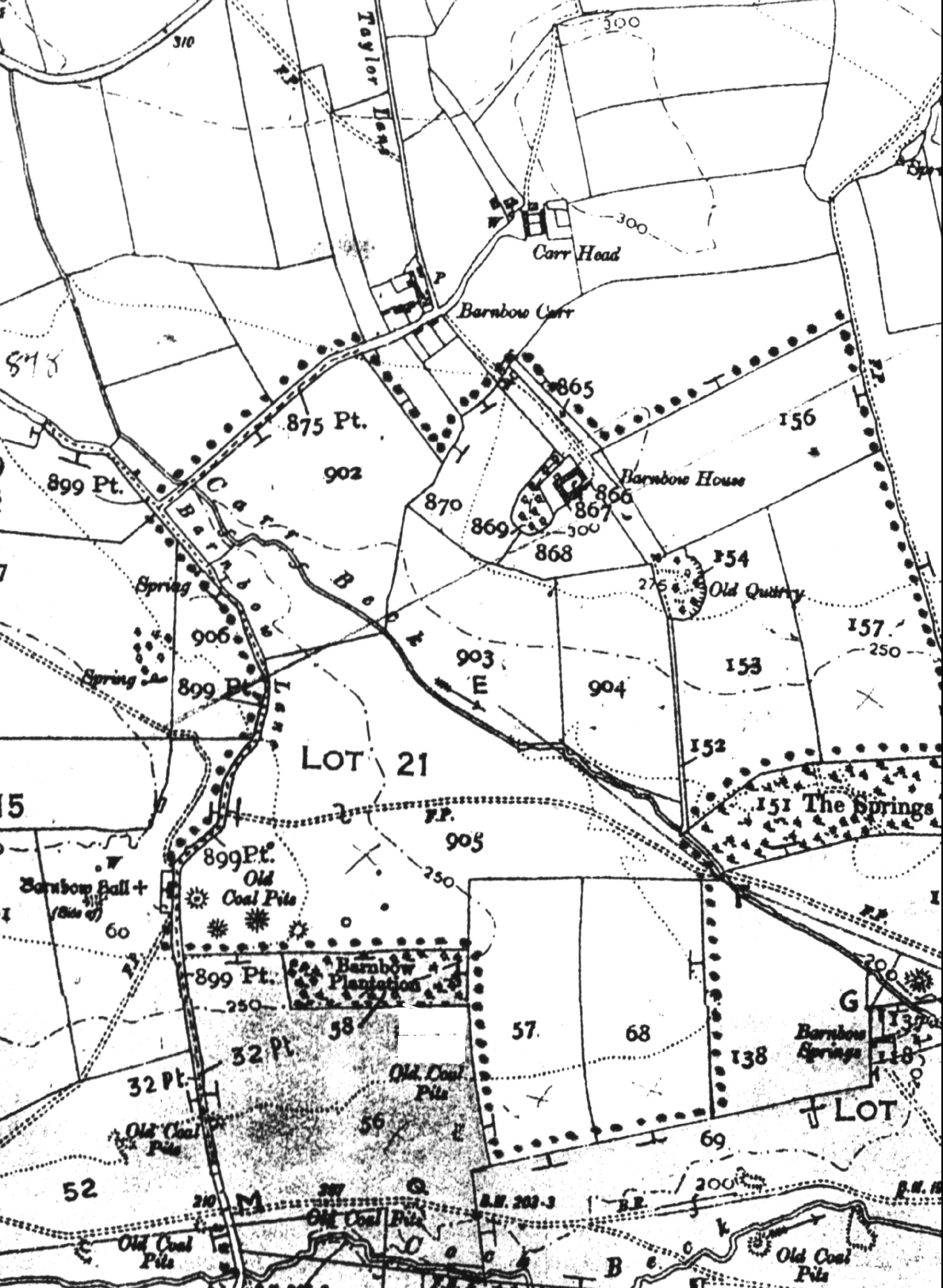

Barnbow is an area of undulating land

lying to the south of the main road from Barwick

to Stanks. At the present time there is only a

handful of dwellings there but in previous

centuries there was a much larger settlement.

The history of Barnbow in those earlier years can

be discovered only from scarce documents that

were written at the time, then preserved and are

now made available to us. They almost invariably

concern money and property. They were not

written to tell us what Barnbow was like in those

days but they are the only sources we have which

give us any inkling of the lives of the

inhabitants at that time.

Barnbow is not mentioned in the Domesday

survey of 1086 but would have formed part of the

manor of Ledston, Kippax and Barwick which is

described there. Formerly the property of the

Saxon lord Edwin of Mercia, the manor with many

others was granted to the Norman lord, Ilbert de

Lascy, after Edwin revolted against King William

in 1071. At a later date, the manor was divided

and Barwick (including Barnbow) became a separate

manor.

An inquisition post mortem on the death of

Henry de Lascy in 1258 shows that there were

seven free tenants in Barnbow: Peter Dawtrey (de

Alta Ripa), Richard de Reyneville, Nicholas de

Barnbow, Robert Forester, William Hurttenant,

Henry (?) and Richard Waleys (Walens). They paid

a total rent of £2.12s.4d and 1lb. of cummin.

In 1290 the Dawtrey lands passed in to the

hands of Robert de Grenefeld, the brother of

William de Grenefeld, who became Archbishop of

York in 1304. The Grenefelds were people of

influence and major landowners in the area for

the next two and a half centuries. Rector

Frederick Selincourt Colman in his book 'The

History of the Parish of Barwick-in-Elmet'

(1908), from which much of this chapter has been

composed, includes numerous land transfers in

Barnbow and elsewhere.

On the death of Henry de Lascy in 1308/9,

his lands, including the manor of Barwick, were

incorporated into the vast Lancaster estates

(later the Duchy of Lancaster) following the

marriage of the de Lascy heiress to the Thomas,2nd. Earl of Lancaster. William de Grenefeld,

son of the aforementioned Robert, initially

supported his lord, Earl Thomas of Lancaster, in

a revolt against King Edward II, but withdrew his

support and was granted a pardon on 1 November

1318, "for all felonies and trespasses committed

by him up to the 7 August last, the robbery of

the Cardinal Legate only excepted". What

punishment was meted out to him for this crime

against such a prominent person we do not know

but the Grenefeld family continued to prosper,

unlike Earl Thomas who was beheaded in 1322 for

his part in the revolt.

A detailed survey of the manor of Barwick

dated 4 October 1341 was drawn up on the

instructions of Henry, 3rd. Earl of Lancaster,

the lord of the manor, in the presence of 12

named jurors 'and others'. There is a separate

section in the survey for Barnbow, detailing its

tenants and lands, from which we can infer that

it was a distinct geographical unit or

'territory' within the manor, with its own

boundaries.

There are seven people described as 'free

tenants', namely: Reginald Reynvill; Thomas, son

of William de Grenefeld; Ellen de Grenefeld;

Robert, son of John de Barnebogh; William

Howeson; Thomas de Birne and Nicholas de Scoles.

Thomas de Grenefeld and Robert de Barnebogh were

two of the jurors. Ellen de Grenefeld, widow of

William and mother of Thomas, also held, as a

free tenant, a messuage and 7 acres of land in

Woodhouse in Barwick manor. The Reynvill family

had held land in Barnbow since the early 13th.

century. In a charter dated 1348/9, the above

Reginald is said to be 'of Bernbowe', so he must

have been a resident as well as a land owner.

The free tenants did not own the freehold

of the land but paid rent to the lord for the

property they held, viz. 10 messuages (houses

with their grounds) and 15 bovates of land. A

bovate was a measure of land of about 10-25

acres, depending on the quality of the land. The

total rent collected from the freemen which, as

is often the case in such surveys, does not agree

with the sum of the individual items, is given as

£1.17s.2d., including 1s.4d. for labour services

or 'works.'

There are three men described as

'bondmen', namely: William Morwicke of Barnebogh,

John White and Thomas, son of William de

Grenefeld. They paid rent for 2 messuages, and 2

bovates and 5 acres of land. It will be noticed

that Thomas, son of William de Grenefeld, is in

both lists, indicating that the terms 'free

tenant' and 'bondman' are used as descriptions of

the manner in which they held their land and not

as personal titles. These tenants paid in rent a

total of £1.1s.0d, plus 4d. for works. In

addition to his Barnbow holdings, Thomas, son of

William Grenefeld, rented 3½ acres of land in

Scholes, paying 1s.9d. Both types of tenant had

to pay 'suit of court' when they renewed their

promise of allegiance to the lord and agreed to

accept the customs of the manor.

On their deaths the

tenancy could be passed on to their next of kin

on payment of double rent for the first year. In

contrast to the custom in other parts of the

manor, the free tenants, in addition to the

bondmen, were obliged to carry out specified

'works' or labour services. In Barnbow these

took the form of reaping on the lord's demesne

land, but as there is no mention of such land in

the Barnbow section, we must conclude that the

tenants paid the small sums specified in lieu of

these services. For his works, Reginald

Reynvill, but not apparently the other tenants,

could claim grazing rights, for all his cattle in

the pasture of Little Moor and Brown Moor.

As might be expected from the name, the

bondman had less freedom and more obligations to

the lord than a free tenant. He had to accept

when elected the office of 'reeve', an important

position concerned in the management of the

agriculture of the manor. In order to prevent

any loss of labour in the manor, the bondman's

son was not allowed to 'be tonsured', that is

ordained a priest, or his daugher to marry

without licence of the lord. No doubt there were

other obligations, not stated in the survey.

Barnbow was unusual in that most of the land was

held by free tenants whereas in Scholes village

at that time there were eleven bondmen and no

free tenants.

What can we deduce from the survey of what

life was like for the inhabitants of Barnbow at

that time? There were nine named tenants renting

12 messuages, the surplus three dwellings being

no doubt sub-let to three unnamed tenants. 12

households must have meant a population for

Barnbow at that time of approximately 55, about

the same as Scholes village at the time. Whether

the houses were concentrated in a small hamlet or

whether they formed a more scattered settlement

we do not know. Most would be frail structures

of wood and little evidence of them now remains.

With 17 bovates, perhaps 250 acres of

arable land, agriculture was clearly the main

occupation in Barnbow. These lands would no

doubt be used in an 'open field' system (see 'The

Barwicker No.32), where each tenant cultivated

several long narrow strips of land in the

(usually) three large unenclosed fields. Between

crops and when left fallow, the fields were used

as common pasture for cattle, etc. Evidence for

this method of farming is provided in a land

transfer charter of 1348/9, which refers to "2

acres of arable land in Oldefeld in the common

fields of Barnbow".

To be successful this method of

agriculture required that all the tenants worked

to a strict timetable, followed the customs of

the manor and obeyed the rulings of the manorial

court. It must have led to a great deal of

cooperation between the inhabitants in their

working lives and hence we can speak of the

'community' of Barnbow, as well as the

'territory' and the 'settlement'. Not all this

interaction was neighbourly. In 1303, Robert de Grenefeld sued William de Lasingcroft, for trespass and damage in pasturing 10 cows on

Littlemore, adjoining Lasingcroft, which Robert

claimed to be his pasture. Robert detained the

cows and caused William a loss of £10. The jury

decided against Robert and ruled that he had no

right of pasture there without William's consent.

In his book the Rev. Colman includes

summaries of 14 land charters concerning Barnbow

dating from the mid 14th. to the mid 15th.

centuries. Some were sworn at Barnbow and were

witnessed by prominent men from the manor and

elsewhere. They refer to land in Barnbow and

other places transferred between named people,

some local, some from other parts. As sources of

information concerning what it was like to live

in Barnbow at the time, as either landlord or

tenant, they are of little use. It is from such

sources and other records involving property,

such as wills and surveys, that allowed Colman,

from patient research and not without some

speculation, to draw up a pedigree of the

Grenefeld family covering two and a half

centuries, which he includes in his book.

Henry, 4th. Earl and 1st. Duke of

Lancaster died in 1361 without a surviving male

heir. The Duchy of Lancaster estates, including

Barwick and Barnbow, passed through his

daughter, Blanche, the wife of John of Gaunt,

4th. son of Richard III, to their son, Henry

Bolingbroke. When he took by force the crown of

England to become Henry IV, he was careful to

separate the Duchy estates, of which he had a

firm legal right, from the royal estates, of

which his claim (as a usurper) was much less

strong. This distinction still exists today.

There is no doubt that the Grenefeld

family prospered during the 14th. century. In

the Poll Tax rolls of 1379, William Grenefeld,

the younger brother and heir of the

aforementioned Thomas, is listed with the small

merchants and craftsmen, and is assessed with his

wife at 3s.4d., much the largest sum in the list

for the township of Barwick, which included the

manors of Barwick and Scholes. He is described

as a 'franklyn', usually translated as

'freeholder'. Elena and Johanna Grenefeld are

included as single adult women assessed at 4d.

each. Randolph del Scholes, who may have been

related to the aforementioned Nicholas, is

assessed with his wife at the lower limit of 4d.,

as are the great majority of married couples.

On 2 February 1385/6, William Grenefeld, the

franklyn, and his son John, with others, were

responsible for the killing of William del Kyrke

of Barnbow. We do not know the details of the

case but William received a royal pardon on 11

May 1389, whereas his son had to wait another

five years until 4 March 1394 for his pardon.

The Grenefelds seemed to live dangerously but

they continued to prosper.

It was in 1424/5, while the youthful Henry

VI, grandson of Henry IV, was lord of the manor

of Barwick, that another survey was made. With

regard to the property described, the survey

differs little from that of 1341. The same

messuages and land can be identified as the names

of the 1341 tenants are given. In 1424/5, 10

messuages and 15 bovates were held by only four

free tenants. John Grenefeld, son of William the

'franklyn' of 1379, had increased the family

holding to 6 messuages and 8« bovates of land,

and had clearly become the dominant landowner in

Barnbow.

Another free tenant, William Kynston, was

the chaplain to the chantry chapel in Barwick

church. He also held a messuage in Kirkgate,

Tadcaster. In the Barwick township poll tax

returns of 1379, he is included as a single man

and paid 4d. in tax. Thomas Kynston, a

carpenter, who may have been William's father,

and Robert Kynston, a cobbler, are included in

the small merchants and craftsmen section of the

returns and are assessed with their wives at 12d

each. Another free tenant holding a messuage and

a bovate of land in 1424/5 was Nicholas

Gascoigne, of Lasingcroft, a member of the family

which would furnish the lords of the manor of

Barwick two centuries later. The fourth free

tenant was Henry Sourby, who held a messuage and

three bovates of land.

2 messuages and 2 bovates of land were

held in 1424/5 by only one bondman or villein,

John Marshall. He also held land in Scholes and

is described as 'of Barnboghe' so he was clearly

a resident there. John Willeson and William

Johnson Diconson, probably residents of Scholes,

held jointly 5 acres of land by lease for a fixed

number of years. The total rent paid to the lord

of the manor by the Barnbow tenants was œ3.0s.4d,

very little change from 1341.

The survey lays out again in detail the

'works' or labour services but it is unlikely

that they were carried out but would have been

exchanged for the small sums quoted. The other

conditions for the free tenants and the bondmen

are give as before, but one wonders how much they

were applicable as by then the manorial system of

land holding was breaking up. The survey shows

that the population of Barnbow and the amount of

arable land had changed little since 1341,

despite the ravages of the Black Death of 1347

and other epidemics.

Whether Barnbow Hall, the seat of first

the Grenefeld and then the Gascoigne families,

was built at this time we do not know. It was

situated on rising ground facing south over the

still pleasant prospect of the valley of the Cock

Beck. Before its demolition in 1721/2, it was a

house of considerable size. Little is now

visible of the hall, as agriculture and the

construction of the reservoir for the Barnbow

munitions factory during World War I have almost

obliterated the last remnants.

In the lay subsidy returns of 1524, which

record taxes paid to finance the foreign wars of

Henry VIII (see 'The Barwicker' No. 1March 19866), John

Grenefeld, grandson of the John Grenefeld in the

1424/5 survey, was assessed for tax on land

valued at œ20 and he paid 20s. Henry Ellis of

Kidall was assessed for a similar sum. They are

both described as 'gentlemen', a place in the

social order reserved for those who did not have

to resort for their income to manual work. They

were the wealthiest men resident in Barwick

township at the time.

John Grenefeld, the last of the family to

bear the ancient name, died at a great age on 6

January, 1540/1. At the time of his death he

held in Barnbow the capital messuage (Barnbow

Hall), three other messuages, two cottages, 40

acres of arable land and 18 closes of meadow and

pasture, for which he paid rent to the lord of

the manor. He held, as the sub-tenant of William

Gascoigne, five messuages, 40 acres of arable

land, 80 acres of meadow, 70 acres of pasture

'with appurtenances'. He also held other land in

Yorkshire.

It is clear from the way that the arable

land is described in the record as separate from

the pasture and meadow, that the old system of

open fields had been abandoned in Barnbow and

that the land had been enclosed. The amount of

the very valuable meadow land, used for the

provision of hay for winter fodder, indicates the

wealth of the Grenefeld estates at this time.

John Grenefeld outlived his two daughters

and his estates went to their two sons, Nicholas

Girlington and John Newcomen, who was married to

Alice daughter of John Gascoigne of Lasingcroft.

In 1548, Nicholas Girlington brought an action

against Thomas Hardcastle and others who "with

staves and other weapons in a riotous manner

wrongfully entered into a meadow called Lentyng

and other closes and expelled the plaintiff".

Hardcastle replied that John Grenefeld had

surrendered the premises to a forebear of his and

that he had enjoyed the use of the premises for

many years. The case was lost.

In the four court cases listed here,

prominent men from Barnbow were prepared to

indulge in violent behaviour to maintain their

position and their property. This was not

however a lawless society as in the the cases

listed, the appropriate legal action was taken to

resolve the matter. Despite living dangerously at

times, the Grenefeld family had prospered during

their two and half centuries in Barnbow.

In 1548, Nicholas Girlington sold his

share of the estate to this cousin John Newcomen.

In 1568, the latter sold Barnbow Hall and its

appurtenances to Richard Gascoigne, his wife's

brother, who a year later acquired the remainder

of Newcomen' s interest in Barnbow and the rest

of the old Grenefeld estates in the parish. The

Gascoigne family were to remain major landowners

in Barnbow until the 20th. century.

| ARTHUR BANTOFT |

Back to the top

Back to the Main Historical Society page

Back to the Barwicker Contents page

Part 2 of the article

.