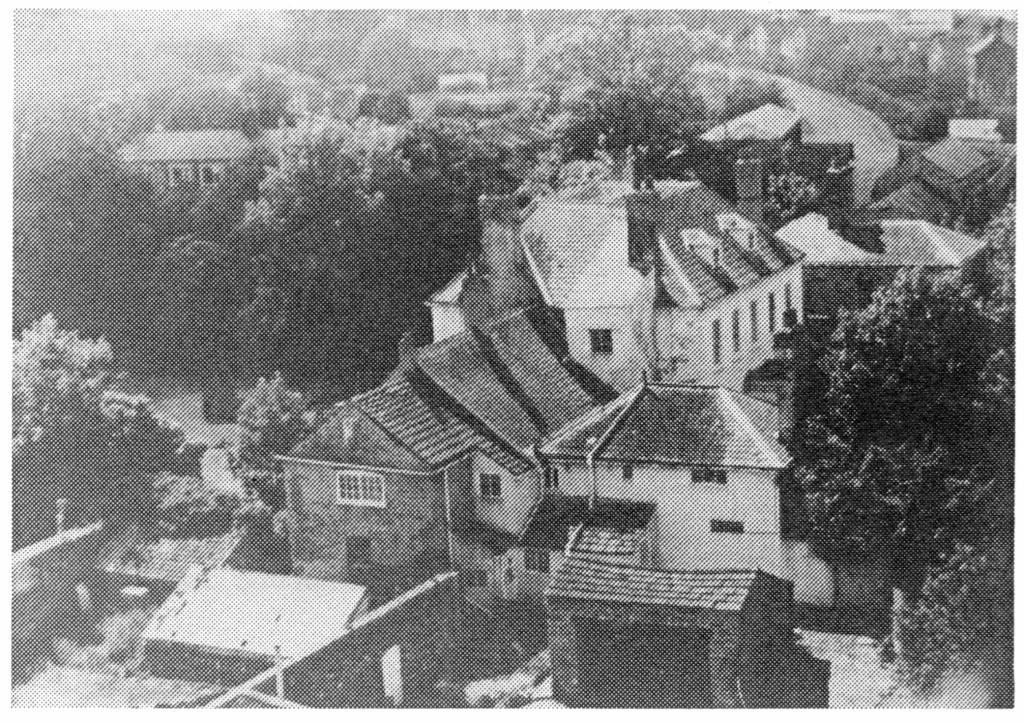

| 12th.-15th. Centuries (2 examples). Colman in his book states that sections of the church, including the chancel and parts of the nave date back to the early part of the 12th. century making it the oldest building in the village. The book contains a plan of the church drawn by Henry Chippindale, an architect member of the Scholes brick-making family. This indicates that the remainder of the nave was 14th. century and the tower and porch were added in the 15th. century. The 15th. century also saw the building of the east end of the old Rectory (see photo opposite). This was thought to comprise a two-storey dwelling used by the incumbent of the time. It would seem likely that there would have been an earlier priest's residence at or near this site. 16th. Century (4 examples). It is thought that the old shop and the adjoining two houses in Main Street referred to in Part 1 were of this century. However major alterations had been carried out probably in the 18th. and 19th. centuries. Glebe Farm which stood at the south end of Main Street was probably of this period and had also been altered in later years. 17th. Century (8 examples). Many people will have seen the stone head over the door of No.6, The Boyle bearing the inscription 'Anno Domini 1674' which suggests that the three houses in this block might be of that date. Other properties probably of this period were Nos. 34-36 Main Street and the old Post Office and two cottages in The Boyle. All had been renovated subsequently. The post office and one of the cottages in The Boyle were demolished 50 or 60 years ago. 18th. Century (95 examples). The majority of the Group D limestone cottages are thought to have been built towards the end of the century together with 7 or 8 others and the Windmill built of hand-made bricks. There were also around 20 Group C properties mainly in limestone, comprising farmhouses and the homes of various tradesmen. The main centre section of the old Rectory was built in 1705. 19th. Century (43 examples). Included in this period are the old school and schoolhouse in Aberford Road, the dozen or so sandstone houses already mentioned, some 25 limestone Group D cottages and the old Chapel. Also towards the end of the century several houses were built with machine-made bricks which were coming into use at that time and were to become the most widely used walling materials for the next 100 years. |

|

| The Old Rectory showing the 15th. Century East End |