|

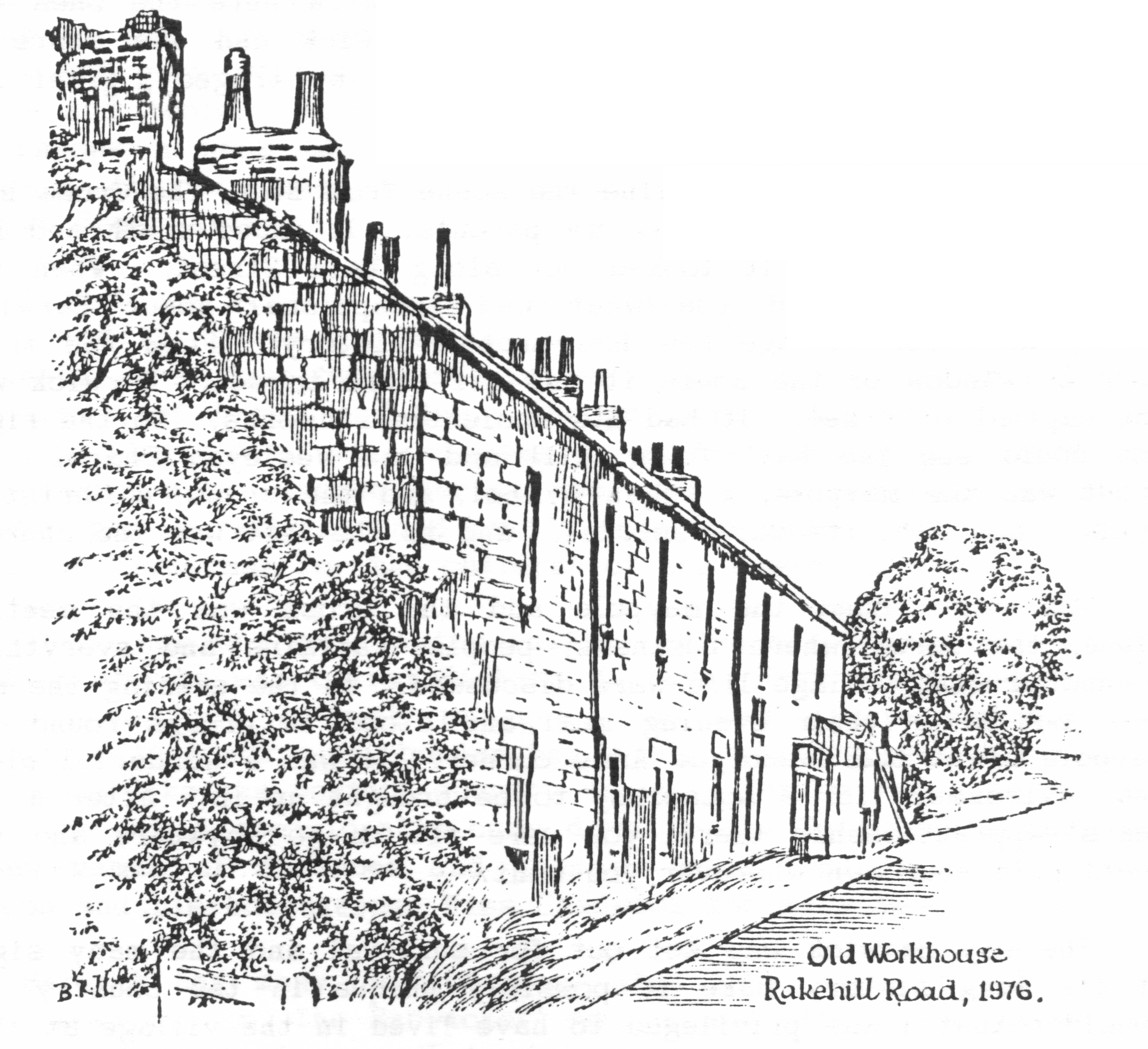

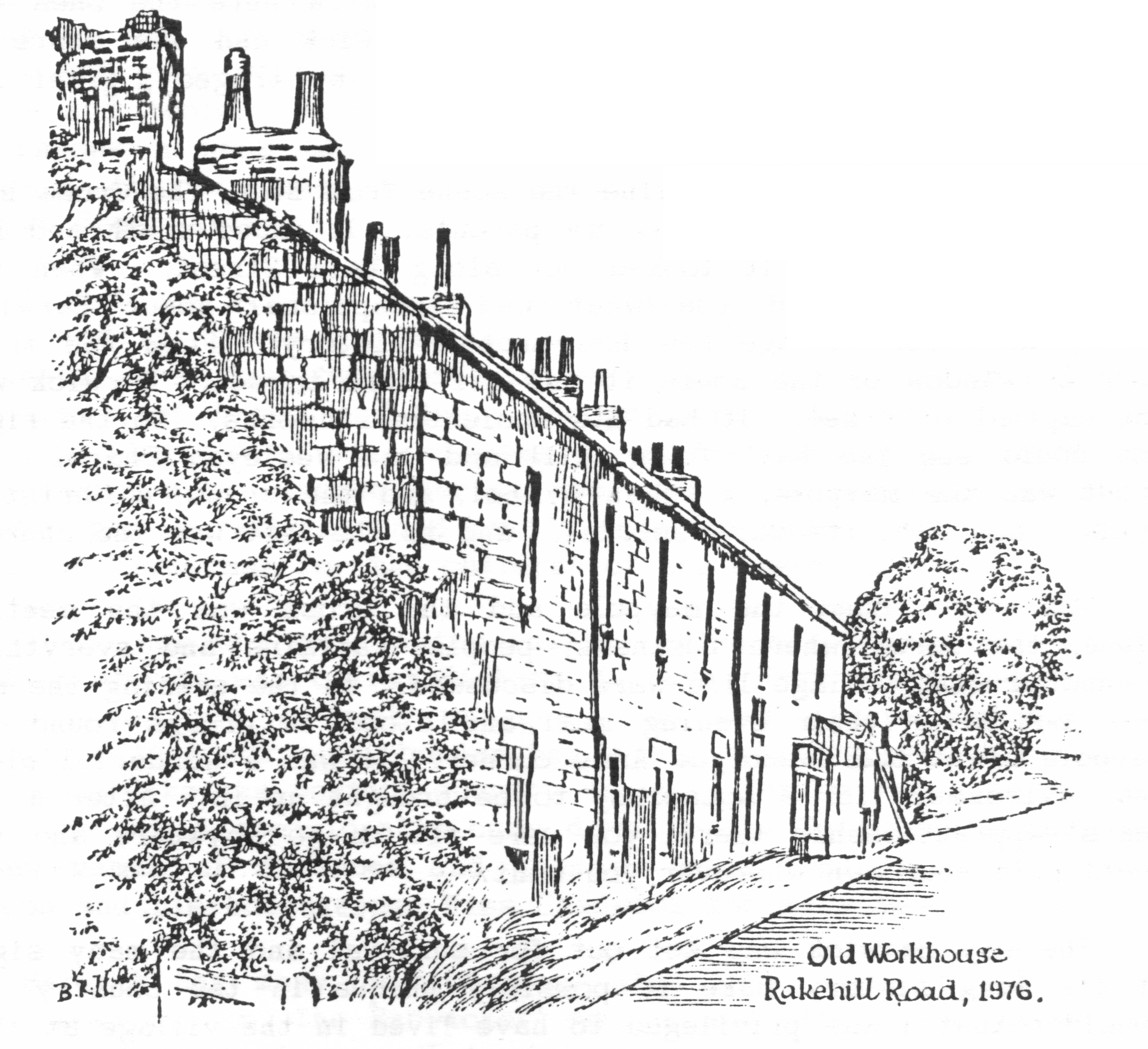

| Pen Sketch by Bart Hammond |

|

| Pen Sketch by Bart Hammond |

| 'The bearer, John Stead, is a drunkard and a beast and the worst of all worsts. Keep him strictly to the rules and send him to the House of Correction in Wakefield if you can. Take care not to let him know of this because we expect to be beholden to him at a sessions trial." |

| "John Marshall was reprimanded for absconding from the house and promised never to repeat the offence. |

| Harriett Potterton was reprimanded for the same offence and conducted herself with great insolence. |

| Samuel Summerton was called up and admonished not to quit the premises again without permission." |