Back to the Main Historical Society page

Back to the Barwicker Contents page

A Mediaeval Pottery Kiln

from The Barwicker No.27

September 1992

In a previous article (see 'The Barwicker' No.22) I described

Potterton Grange Farm when I and my husband lived there from 1959

to 1973. In about 1960, I tried to make a garden on the area to

the south of the house but I found myself digging up a number of

whole or broken earthenware objects like plant pots. I used five

of them to grow plants in, not then realising their archaeological

importance.

One day in the summer of 1962, a gentleman called and asked if

he could have permission to look along the edge of the top field

leading from the farmhouse to Morgans Cross. He had found some

pieces of the earthenware objects which I later discovered were

called 'saggars'. I took him and showed him where I had dug up the

saggars and I explained that I was trying to dig

a garden. He looked at me and said, 'Please, please, please, don't

dig any more'.

|

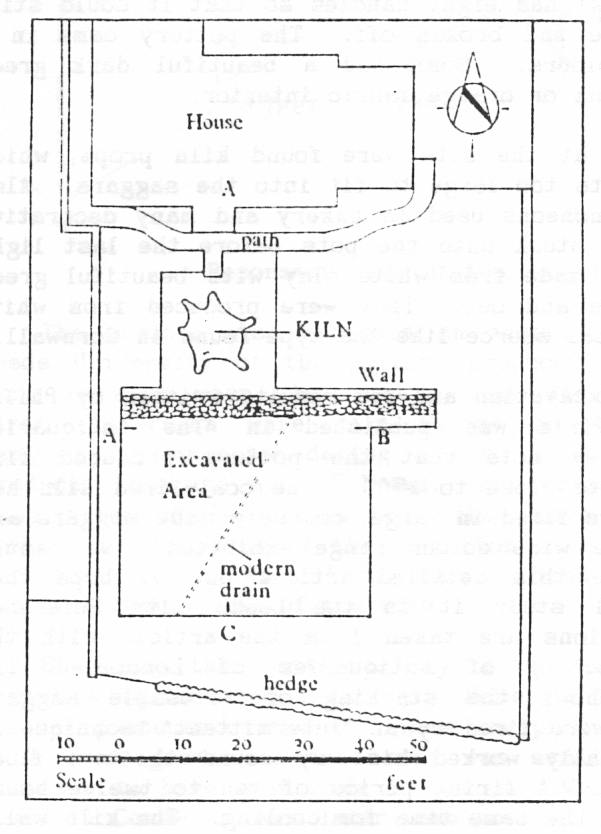

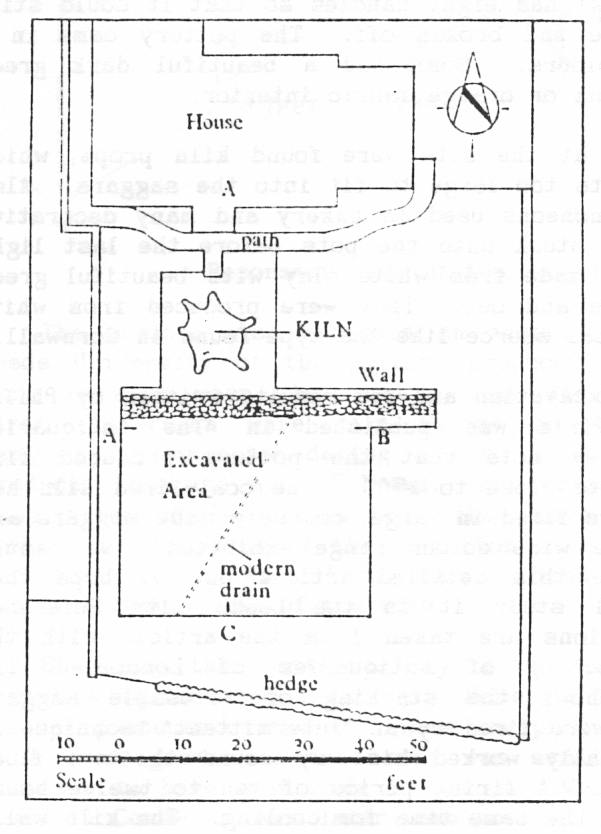

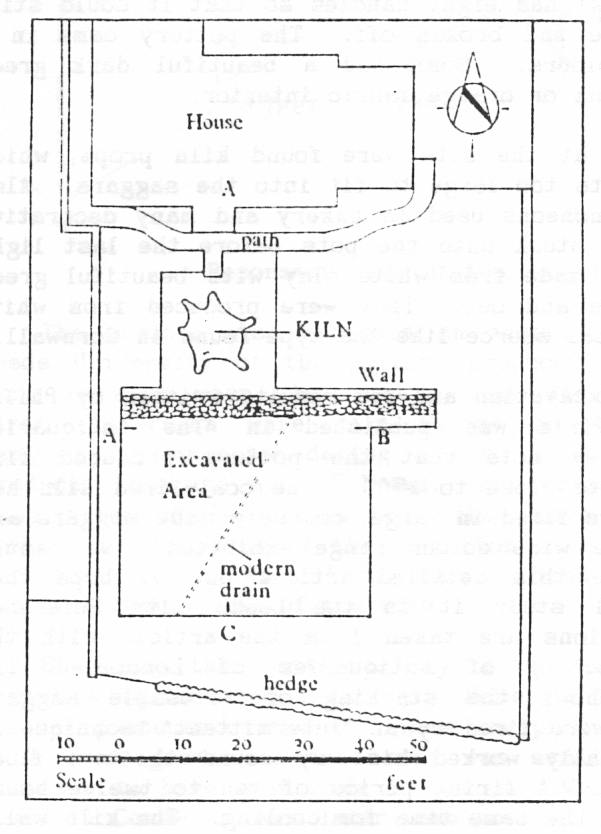

| Site location |

He was Philip Mayes from Leeds University and he was so excited that when he tried to explain, he went into so much historical

detail that it went over my head at first and I could not visualise what he was talking about.

He asked if he could excavate the site and following a family conference, the plan

was agreed. All the top soil was removed from the site and tipped onto the

garden to the east side of the area investigated. The excavation revealed a

late mediaeval pottery kiln.

I was surprised to learn that the kiln had been fired with

coal, which was shown when the coke debris was sent to London and

centrifugally spun to separate it. Scientific dating showed that

the kiln was last fired in about 1500. The kiln was shaped like a

beehive with a vent at the top. The pots were fired inside the

saggars which were turned upside down from the way I had used

them as plant pots. The saggars protected the pots during the

firing. The pieces of pot dug out were investigated by Hiss Pirie

of the Leeds Museum. In the evening or at weekend we would sit

round our kitchen table and she would look at the pieces I had dug

up. It was a real privilege to sit and watch her at work as she

fitted pieces together to make a part or a whole pot.

The pots were of many different shapes and sizes. One

incomplete jug was about 18 inches high and when I asked Miss

Pirie what it would be used for she said it was a water carrier.

The pots were what is called Cistercian ware. There were some

multi-handled drinking vessels, which were made because the

Cistercian monks had a rule that they must use two hands when

drinking. One small bowl had eight handles so that it could still

be used even after some had broken off. The pottery came in a

surprising range of colours. Some had a beautiful dark green

external glaze over a pink or orange fabric interior.

Amongst the debris at the site were found kiln props, which

were used to support pots too large to fit into the saggars. Also

found were pieces of pancheons used in bakery and many decorative

oval 'slips', which were stuck onto the pots before the last light

firing. Some pots were made from white clay with beautiful green

or yellow glazing inside and out. They were produced from white

clay from an unknown local source like the type found in Cornwall.

An account of the excavation and its results written by Philip

Mayes and Elizabeth Pirie was published in 'The Antiquaries

Journal' of 1966. They note that the pottery produced fine

Cistercian ware at a date close to 1500. The coal-fired kiln had

six flues. The pots were fired in large, coarsely-made saggars and

were remarkable for the wide colour range exhibited. We cannot

satisfactorily summarise this detailed article but we hope that

interested readers will study it in the Leeds City Reference

Library. The illustrations are taken from the article with the

permission of the Society of Antiquaries of London. The

reconstruction below shows the stacking of re-usable saggars

within the kiln, which were fired by an 'intermittent' technique in

which the stoker gradually worked his way round the six flues

adding coal as required. A firing period of ten to twelve hours

was probable with about the same time for cooling. The kiln walls

were then broken to remove the pots in their saggars. It was

rebuilt for the next firing.

The article also includes an account by Jean Le Patourel of

Leeds University of the pottery produced. The importance of the

work is seen when she reports that the Potterton kiln was the

first Cistercian ware kiln to be completely excavated, to be

sampled for magnetic dating and to have the whole range of its

products recorded and analysed. Her article has diagrams of the

many types of Cistercian ware that have been found, not all at

Potterton. Products of the Potterton kiln have been recognised at

Kirkstall Abbey. Rest Park. Chapel Haddlesey and Newstead. all

within fifteen miles of the site.

She notes that Potter ton may be regarded as a specialised kiln

wi thin a specialised industry. Some of the most unexpected and

unusual products of the kiln were the products of white clay. Part

of a chafing-dish in this clay was similar to dishes originally

presumed to have been made in France. White clay. similar to that

found in Cornwall. was later used in the manufacture of the famous

eighteenth century 'Leeds ware'.

Back to the top

Back to the Main Historical Society page

Back to the Barwicker Contents page