|

|

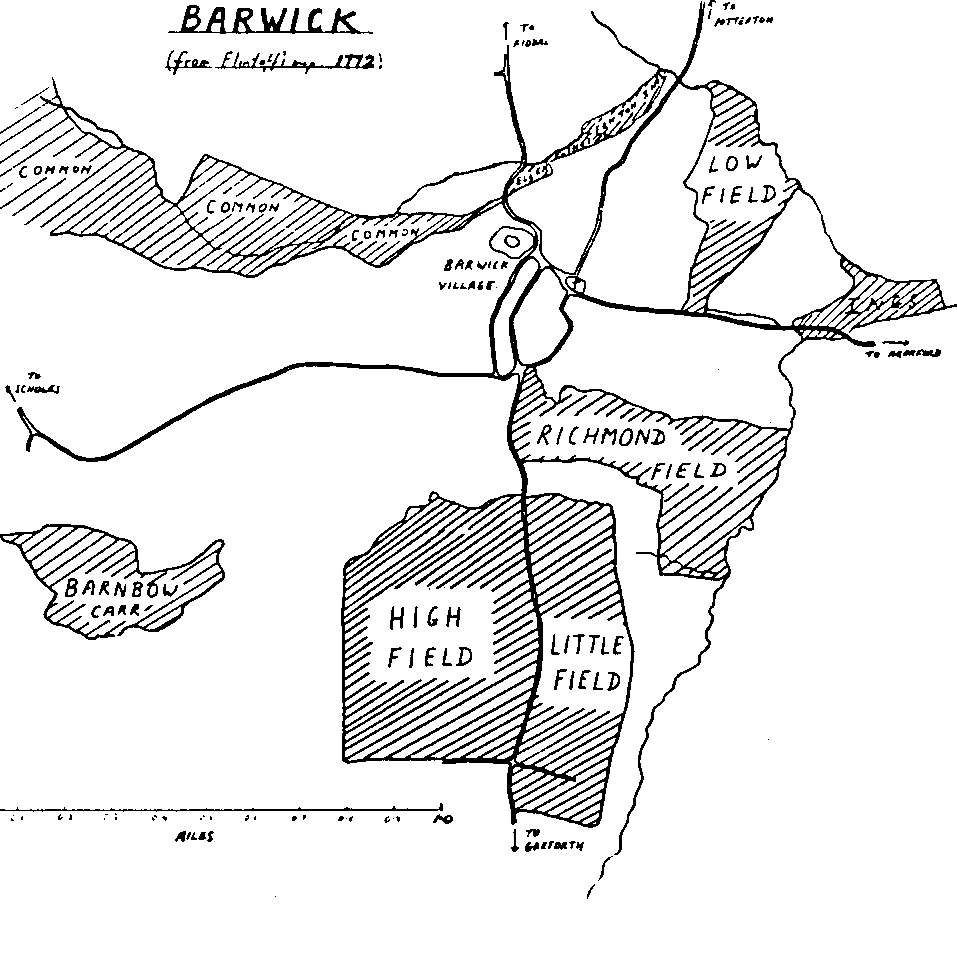

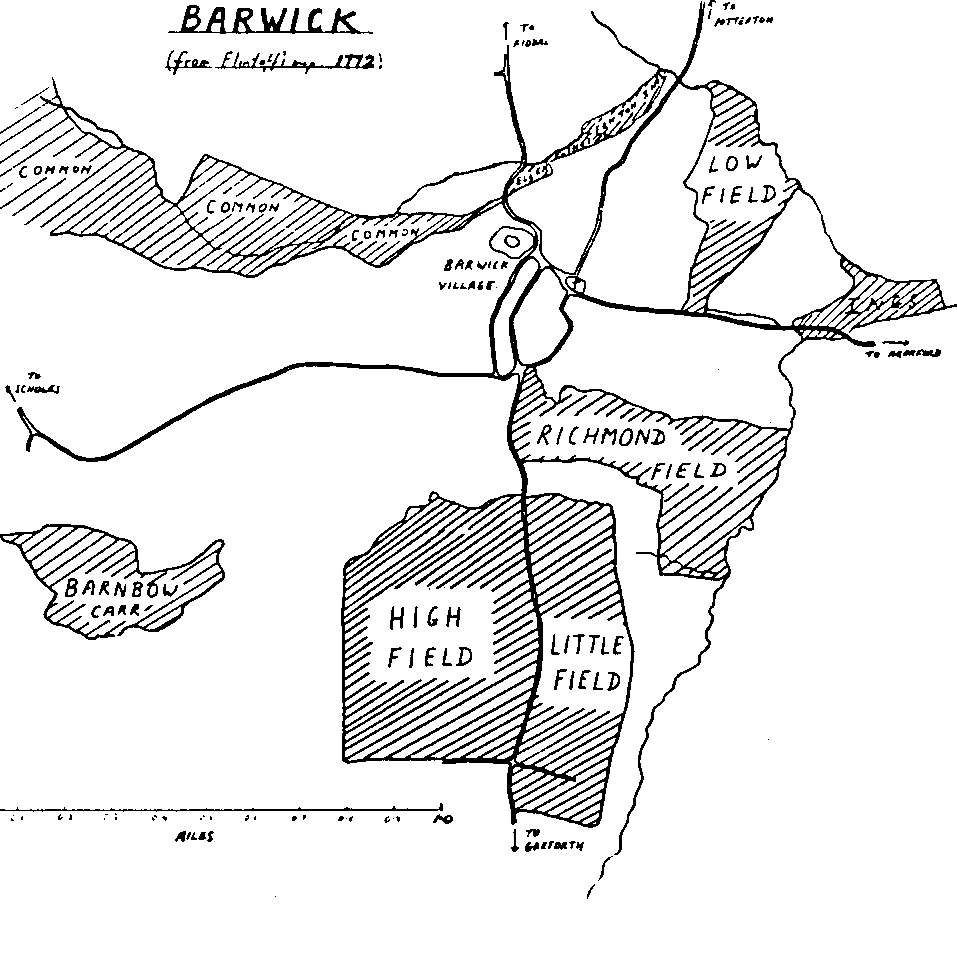

| (1) Open Fields. There were several of these large fields in Barwick, each probably occupying more than a hundred acres. Some names remain: High Field, Low Field, Richmond Field and Little Field. Each Held was divided into strips, called selions or lands, of perhaps an acre in area. A collection of strips running parallel to one another was called a furlong or, more commonly in these parts, a flat. Each peasant farmer worked several strips in each field, which grew a single crop of barley, oats, peas and beans or was left fallow. The crops were rotated each year. After the harvest, the field was used as common grazing land. |

| (2) Commons. This was land which had not been cultivated. It provided rough grazing for cattle, geese, etc. and was used for the collection of wood or turf for fuel. It was sometimes called waste. |

| (3) Ings. These were meadows near streams. How the hay produced was allocated to individual farmers in Barwick in medieval times is not known. Much later, in 1764, the Rector had two parcels of land in Barwick Ings; these were termed "a six day mowing" (six acres) and "a one day mowing" (one acre). In 1716, the Town Book lists 11 persons having a total of 67 beastgates in Barwick ings. A beastgate allowed a person to graze one cow on the land, after haymaking. The Rector had 16½ beastgates. Another miracle? |

Total area of the township | 6934 acres | 100% |

Open Fields | 601 acres | 8.5% |

| Commons and Wastes | 1934 | 28% |

| Ings | 28 | 4.5% |

| (1) Highways, such as York Road, |

| (2) Private roads and public bridleways, such as Miry Lane, and several "occupation roads" which gave farmers access to their land, and |

| (3) Footroads, which form our present rights of way. |

ARTHUR BANTOFT |