The Medieval Settlement of Hillam Burchard

from The Barwicker No.4

Back to the Main Historical Society page

Back to the Barwicker Contents page

In Edition No.1 of "The Barwicker" brief reference was made (on page 7) to the medieval settlement of Hillam and a water-mill of the same name, both sited in the valley of the Cock Beck, close to Parlington.

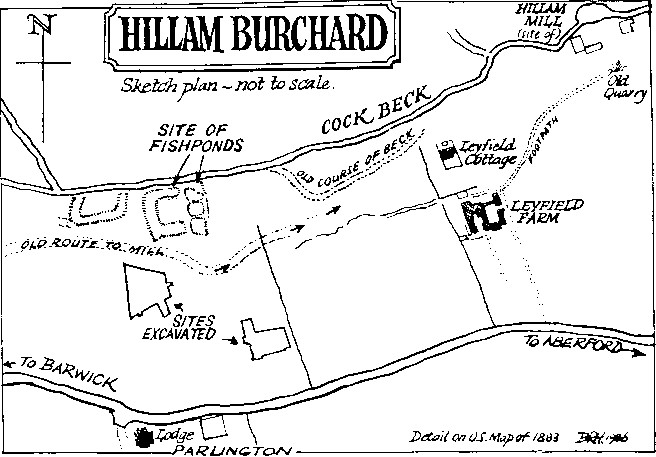

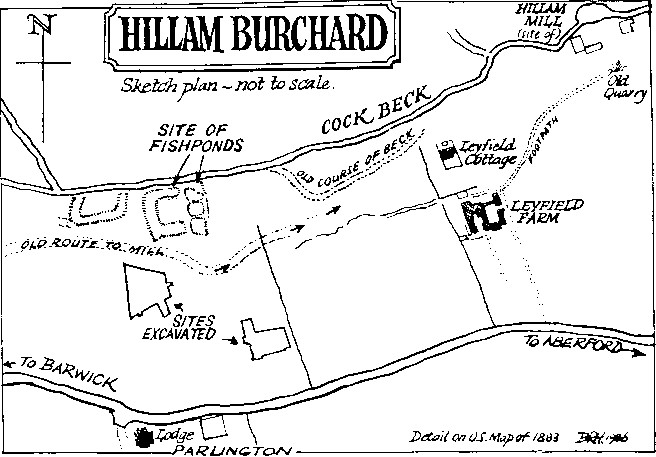

Details of Hillam Burchard were identified initially from documents which referred to the former existence of a settlement of that name in the northern part of Parlington township. The name Hillam (which no longer exists in the area) means '(on) the hills', and no doubt relates to the two areas of banked enclosures on the south side of the Cock Beck, some 600 metres east of Ass Bridge. The second part of the name (Burchard) was taken from Pain, son of Burgheard, a twelfth century owner of Hillam, and the probable ancestor of the Despenser family.

The opportunity to investigate the site of the abandoned settlement arose in 1979 when the land containing the main earthworks was ploughed for the first time in living memory, unearthing number of artifacts, including large quantities of pottery ranging in date from the twelfth to early fifteenth century. Excavations (by the West Yorkshire Archaeological Unit) revealed that a sequence of dwellings and other buildings had occupied the site at a later date to be succeeded by a 'thackstone' quarry and lime kiln, all abandoned by the fifteenth century.

It was evident that the overall area of the settlement had at one time extended across Aberford Road onto land on the south side, not far from Parlington Lodge. The plan of the area excavated indicated that, over the period of occupation, a number of phases of building had taken place, on different alignments. Although few traces of the original foundations survive, a complete well-laid rectangular hearth stone was found standing 23 cms proud of the present surface, and this was no doubt part of a major building, of which no other evidence was found.

A large quantity of pottery of twelfth to thirteenth century ate was recovered from pits used for depositing rubbish by the former inhabitants, and the quality of some remains of the domestic pot-ware tends to indicate the presence in the early settlement of upper class residents.

A large stone slate, or 'thackstone', quarry had been dug into the side of the valley and across what appears to have been the main entrance to the (then abandoned) eastern part of the settlement.

The quarry, extended down through the outcrop of limestone capping, and into the low-graded laminated sandstone, slabs of which were used as roof slates or 'thackstones'. Many large fragments of stone slates in various stages of rough cut were found in the quarry fill. The uncovered quarry face presented a stepped appearance as a result of the breaking out of large blocks of stone which could be stored over winter to weather naturally, making the stone each easier to split by the slate maker. The earthworks of the quarrymens' workshops and weathering areas were not located but probably lay nearby.

A contemporary near-complete lime-burning kiln lay adjacent to the quarry. This had been dug into the natural slope down the sandstone beds, and the battered walls of the kiln were made from unmortared limestone blocks. The products of this small industrial complex do not appear to have been used anywhere on the site, indicating that the quarry and the kiln were used to supply materials for other buildings in the area.

There is evidence that a water mill was located within the limits of the settlement, together with a millpond which would drain to the nearby Cock Beck. Another interesting feature of the Hillam site is the fishpond complex on the south side of the beck. The western part has previously been identified as a moated enclosure, but a detailed survey of the area shows that it is part of a fishpond layout through which water from the Cock Beck was at one time diverted. The water from the fishpond outlet was returned to the beck by means of a weir. Enclosures and building platforms associated with the complex may have been the fish curing plant. The fishponds would be the property of the lord of the manor at Parlington, and although they happened to be situated close to the settlement, the local inhabitants would not be entitled to help themselves to the fish.

The significance of the fishponds is related to the fact that fish formed a major part of the diet of the upper class during the Middle Ages, the high price of all varieties restricting its consumption to those who could afford it. Due to the distance from the nearest coastal water, the inhabitants had to be content with dried or salted fish or breed their own. In the Middle Ages fish breeding facilities were attached to both lay and monastic holdings, usually located on secondary streams which provided s constant flow of running water, and this latter condition would have been a major factor in siting the fishponds at Hillam.

Sketch by Bart Hammond

Some distance to the east of Hillam settlement lies the site of an abandoned water mill, and a terraced way running along the south bank of the Cock Beck indicates a section of the route which was once used to convey corn and other materials from Barwick to the mill. The line of the original mill route was diverted during the building of the Hillam settlement and the later route can still be identified from aerial photographs, where it crossed the earthworks of the abandoned settlement.

The mill way would have needed to provide free access along its entire length, with no obstacles such as stiles, to enable the manorial tenant to transport his grain to the mill, and flour tack. The principal form of transport in these times was the horse and routes leading to the water mill had to be wide enough to allow carts and wains to frequently deliver large quantities of timber and stones required to repair the mill, dam and goit.

The water mill, known as Hillam Mill (in more recent times referred to as Becca Mill) was founded by a charter of John de Lasey, Constable of Chester, early in the thirteenth century. In 1235/5 it was granted by the King to Hugh le Despenser, Lord of Parlington, and Barwick tenants were compelled to grind their corn at the mill.

Hillam Mill became disused in the latter part of the nineteenth century, but remains of the buildings are still visible to the south of the concrete-sided goit (diverted water channel) which now forms the line of the Cock Beck. The original stream course forming the boundary between the townships of Parlington and Aberford, lies to the north of a boggy meadow of the former beck. Earthworks near the water mill site may be the remains of the miller's house and outbuildings.

The mechanism of the water-mill could take two different forms, determined by the method of driving the water wheel and the position of the main drive shaft. The system used would be decided by the head of water available. The most common system found in medieval England was the horizontal mill, with a vertical wheel and horizontal drive shaft which drove, through two cogs operating at 90° to each other, a pair (or pairs) of stones. The method used to drive the Hillam Mill would probably be by an overshot wheel, where the lower part of the wheel lay in the water course.

As mentioned earlier, the corn-mill was the property of the lord of the manor and the servile tenants were obliged to grind their corn at the mill specified by the landlord to whom they owed allegiance. The mill was one of the most profitable features of the manor because of the landlord's monopoly. One of the 'paines' formerly levied in the manors of Barwick and Scholes stated:-

The Lord's monopoly of corn grinding was frequently broken, and this was considered a serious offence, not necessarily because of the obligation of servile tenant, but more seriously it deprived the landlord of income.

There is ample evidence that the landlord's claim to the c grinding was rigidly enforced.

In 1673 Thomas Gascoigne sued Richard Vevers, of Potterton the Duchy Court to compel him to grind his melt at Hillam Mill.

Gascoigne stated that no person should erect any water corn mills, windmills, handmills, horse mills or other mills within manor, nor should they take corn out of the manor to be ground elsewhere, and that Richard Vevers the elder, William Vevers his son, William Ellis, George Spink, and William Bridges, refused bring their corn.

For the defence it was contended that Hillam Mill was not within the manor of Barwick, but that of Parlington. Judgment was given in Gascoigne's favour, and on October 1674, Richard Vevers paid him 'four broad pieces of gold' for refusing to grind his malt at the mill. Documentary evidence makes it clear that the mill at Hillam, continued as the demesne mill of Barwick until the nineteenth century.

There is still much of interest to be learned of life and conditions in medieval hamlets such as Hillam Burchard, and it is hoped there will be opportunity to produce a further article on this topic in due course.

Back to the Barwicker Contents page

In Edition No.1 of "The Barwicker" brief reference was made (on page 7) to the medieval settlement of Hillam and a water-mill of the same name, both sited in the valley of the Cock Beck, close to Parlington.

Details of Hillam Burchard were identified initially from documents which referred to the former existence of a settlement of that name in the northern part of Parlington township. The name Hillam (which no longer exists in the area) means '(on) the hills', and no doubt relates to the two areas of banked enclosures on the south side of the Cock Beck, some 600 metres east of Ass Bridge. The second part of the name (Burchard) was taken from Pain, son of Burgheard, a twelfth century owner of Hillam, and the probable ancestor of the Despenser family.

The opportunity to investigate the site of the abandoned settlement arose in 1979 when the land containing the main earthworks was ploughed for the first time in living memory, unearthing number of artifacts, including large quantities of pottery ranging in date from the twelfth to early fifteenth century. Excavations (by the West Yorkshire Archaeological Unit) revealed that a sequence of dwellings and other buildings had occupied the site at a later date to be succeeded by a 'thackstone' quarry and lime kiln, all abandoned by the fifteenth century.

It was evident that the overall area of the settlement had at one time extended across Aberford Road onto land on the south side, not far from Parlington Lodge. The plan of the area excavated indicated that, over the period of occupation, a number of phases of building had taken place, on different alignments. Although few traces of the original foundations survive, a complete well-laid rectangular hearth stone was found standing 23 cms proud of the present surface, and this was no doubt part of a major building, of which no other evidence was found.

A large quantity of pottery of twelfth to thirteenth century ate was recovered from pits used for depositing rubbish by the former inhabitants, and the quality of some remains of the domestic pot-ware tends to indicate the presence in the early settlement of upper class residents.

A large stone slate, or 'thackstone', quarry had been dug into the side of the valley and across what appears to have been the main entrance to the (then abandoned) eastern part of the settlement.

The quarry, extended down through the outcrop of limestone capping, and into the low-graded laminated sandstone, slabs of which were used as roof slates or 'thackstones'. Many large fragments of stone slates in various stages of rough cut were found in the quarry fill. The uncovered quarry face presented a stepped appearance as a result of the breaking out of large blocks of stone which could be stored over winter to weather naturally, making the stone each easier to split by the slate maker. The earthworks of the quarrymens' workshops and weathering areas were not located but probably lay nearby.

A contemporary near-complete lime-burning kiln lay adjacent to the quarry. This had been dug into the natural slope down the sandstone beds, and the battered walls of the kiln were made from unmortared limestone blocks. The products of this small industrial complex do not appear to have been used anywhere on the site, indicating that the quarry and the kiln were used to supply materials for other buildings in the area.

There is evidence that a water mill was located within the limits of the settlement, together with a millpond which would drain to the nearby Cock Beck. Another interesting feature of the Hillam site is the fishpond complex on the south side of the beck. The western part has previously been identified as a moated enclosure, but a detailed survey of the area shows that it is part of a fishpond layout through which water from the Cock Beck was at one time diverted. The water from the fishpond outlet was returned to the beck by means of a weir. Enclosures and building platforms associated with the complex may have been the fish curing plant. The fishponds would be the property of the lord of the manor at Parlington, and although they happened to be situated close to the settlement, the local inhabitants would not be entitled to help themselves to the fish.

The significance of the fishponds is related to the fact that fish formed a major part of the diet of the upper class during the Middle Ages, the high price of all varieties restricting its consumption to those who could afford it. Due to the distance from the nearest coastal water, the inhabitants had to be content with dried or salted fish or breed their own. In the Middle Ages fish breeding facilities were attached to both lay and monastic holdings, usually located on secondary streams which provided s constant flow of running water, and this latter condition would have been a major factor in siting the fishponds at Hillam.

Sketch by Bart Hammond

Some distance to the east of Hillam settlement lies the site of an abandoned water mill, and a terraced way running along the south bank of the Cock Beck indicates a section of the route which was once used to convey corn and other materials from Barwick to the mill. The line of the original mill route was diverted during the building of the Hillam settlement and the later route can still be identified from aerial photographs, where it crossed the earthworks of the abandoned settlement.

The mill way would have needed to provide free access along its entire length, with no obstacles such as stiles, to enable the manorial tenant to transport his grain to the mill, and flour tack. The principal form of transport in these times was the horse and routes leading to the water mill had to be wide enough to allow carts and wains to frequently deliver large quantities of timber and stones required to repair the mill, dam and goit.

The water mill, known as Hillam Mill (in more recent times referred to as Becca Mill) was founded by a charter of John de Lasey, Constable of Chester, early in the thirteenth century. In 1235/5 it was granted by the King to Hugh le Despenser, Lord of Parlington, and Barwick tenants were compelled to grind their corn at the mill.

Hillam Mill became disused in the latter part of the nineteenth century, but remains of the buildings are still visible to the south of the concrete-sided goit (diverted water channel) which now forms the line of the Cock Beck. The original stream course forming the boundary between the townships of Parlington and Aberford, lies to the north of a boggy meadow of the former beck. Earthworks near the water mill site may be the remains of the miller's house and outbuildings.

The mechanism of the water-mill could take two different forms, determined by the method of driving the water wheel and the position of the main drive shaft. The system used would be decided by the head of water available. The most common system found in medieval England was the horizontal mill, with a vertical wheel and horizontal drive shaft which drove, through two cogs operating at 90° to each other, a pair (or pairs) of stones. The method used to drive the Hillam Mill would probably be by an overshot wheel, where the lower part of the wheel lay in the water course.

As mentioned earlier, the corn-mill was the property of the lord of the manor and the servile tenants were obliged to grind their corn at the mill specified by the landlord to whom they owed allegiance. The mill was one of the most profitable features of the manor because of the landlord's monopoly. One of the 'paines' formerly levied in the manors of Barwick and Scholes stated:-

| "None shall carry or send any of the corn or grain which they shall use in their houses to any foreign mill to be ground, but shall send same to Hillome Mills, unless it be such corn as they shall buy out of the said Manor." |

The Lord's monopoly of corn grinding was frequently broken, and this was considered a serious offence, not necessarily because of the obligation of servile tenant, but more seriously it deprived the landlord of income.

There is ample evidence that the landlord's claim to the c grinding was rigidly enforced.

In 1673 Thomas Gascoigne sued Richard Vevers, of Potterton the Duchy Court to compel him to grind his melt at Hillam Mill.

Gascoigne stated that no person should erect any water corn mills, windmills, handmills, horse mills or other mills within manor, nor should they take corn out of the manor to be ground elsewhere, and that Richard Vevers the elder, William Vevers his son, William Ellis, George Spink, and William Bridges, refused bring their corn.

For the defence it was contended that Hillam Mill was not within the manor of Barwick, but that of Parlington. Judgment was given in Gascoigne's favour, and on October 1674, Richard Vevers paid him 'four broad pieces of gold' for refusing to grind his malt at the mill. Documentary evidence makes it clear that the mill at Hillam, continued as the demesne mill of Barwick until the nineteenth century.

There is still much of interest to be learned of life and conditions in medieval hamlets such as Hillam Burchard, and it is hoped there will be opportunity to produce a further article on this topic in due course.

Tony Cox.